Leonora Carrington rejected convention at every turn. Her art, writing, and philosophy challenged norms from youth to old age. This week I examine her extraordinary life, her surrealist art, and her concept of 'Survival Kits' - collections of objects and ideas to navigate turbulent times.

"The purpose of these kits is to offset the destructive acts of daily life, to pull us through the hardest times, to reawaken our sense of wonder and to renew our capacity for reverie and revolt."

- Surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, quoted by Penelope Rosemont, 2002

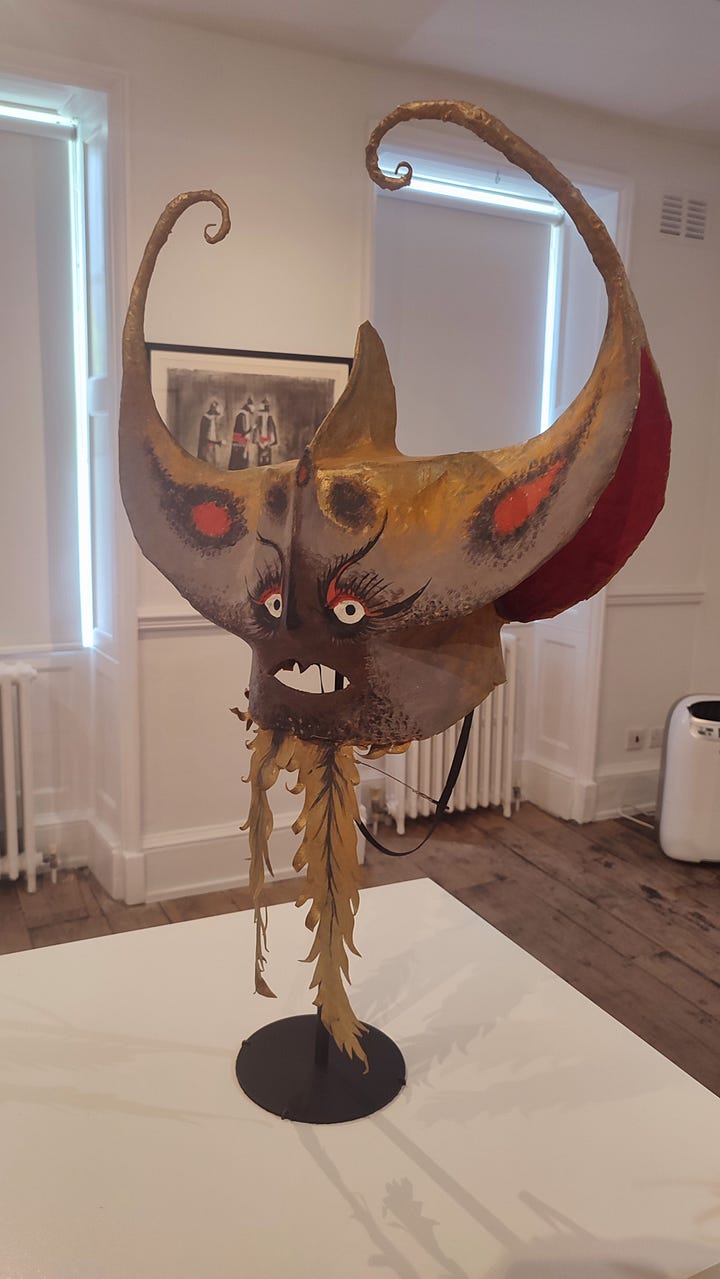

Leonora Carrington is one of my favourite artists. The new exhibition of her art in Petworth contains a "Surrealist Survival Kit." These were collections of poetic, magical, talismanic objects, along with images and other "Surrealist things." A kit might include a feather, a pebble, a piece of glass, or some verses from a poem.

In the 1980s, Leonora was part of the Chicago Surrealist Group. One of its members, Penelope Rosemont, remembers that Leonora was keen on these kits.

As we continue to navigate a challenging world, these Survival Kits should come in handy. What would you keep in yours?

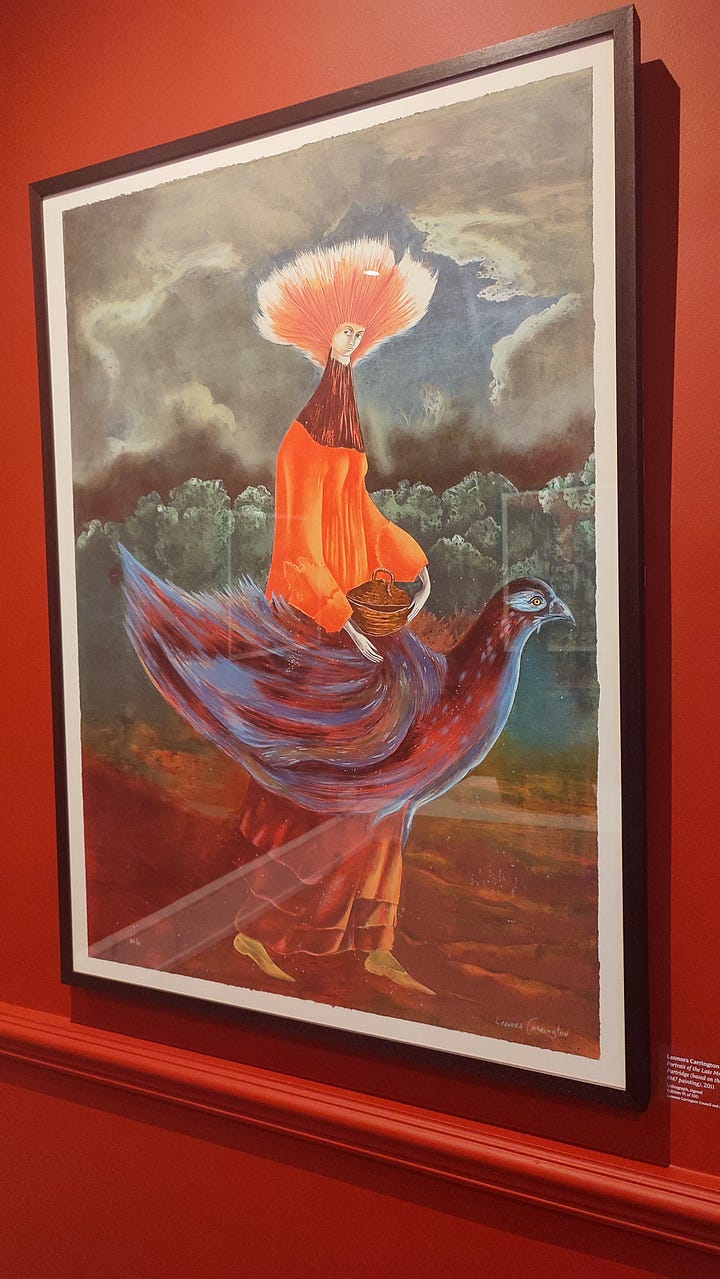

I was first introduced to Leonora Carrington in Mexico City, and then in the jungle town of Xilitla where I saw some of her work and immediately felt a kinship with her. I later acquired a copy of her tarot deck and this weekend went to the new exhibition of her work in Petworth. She was a visionary artist who is finally receiving the credit she deserves.

Leonora Carrington lived a long and fascinating life, and her work reflects her many interests, including feminism, mythology, and the natural world. She was also a rebel, who challenged the expectations of her family and society. Her rebel soul speaks to mine.

Leonora's rebellious spirit was evident from an early age. In her short story "The Stone Door," she writes about a girl who is frustrated by the limitations placed on her because of her gender. "Little girls can't do the same things as little boys, they say. It isn't true," the girl says. "I can kick harder than Gerard and I don't allow him to draw horses."

Leonora's own childhood was marked by similar restrictions. She was expected to follow more "ladylike" pursuits, while her brothers were encouraged to spend time outdoors and playing sports. As a teenager, she was sent to boarding schools, where she continued to rebel against the expectations placed on her.

Leonora fell in love with Max Ernst, a German artist who was 26 years her senior. Ernst was already married, and the relationship caused a scandal. Leonora's father was so outraged that he complained to the police about Ernst's paintings, saying they were pornographic.

To escape the attention, Leonora and Ernst fled to France. They were joined by other Surrealist artists, including Lee Miller, Roland Penrose, and Man Ray. Leonora later said that this was one of the happiest times of her life.

Her time in France was cut short by the outbreak of World War II. Ernst was arrested and detained by the Nazis, and Leonora was forced to flee to Spain. These traumatic events caused her to have a breakdown and was eventually committed to a psychiatric hospital, where she underwent a series of harrowing treatments.

Leonora eventually escaped from the hospital and made her way to Mexico with Renato Leduc, a Mexican poet whom she’d met in Spain and then married. The marriage was short-lived, but Leonora remained in Mexico for most of the rest of her life.

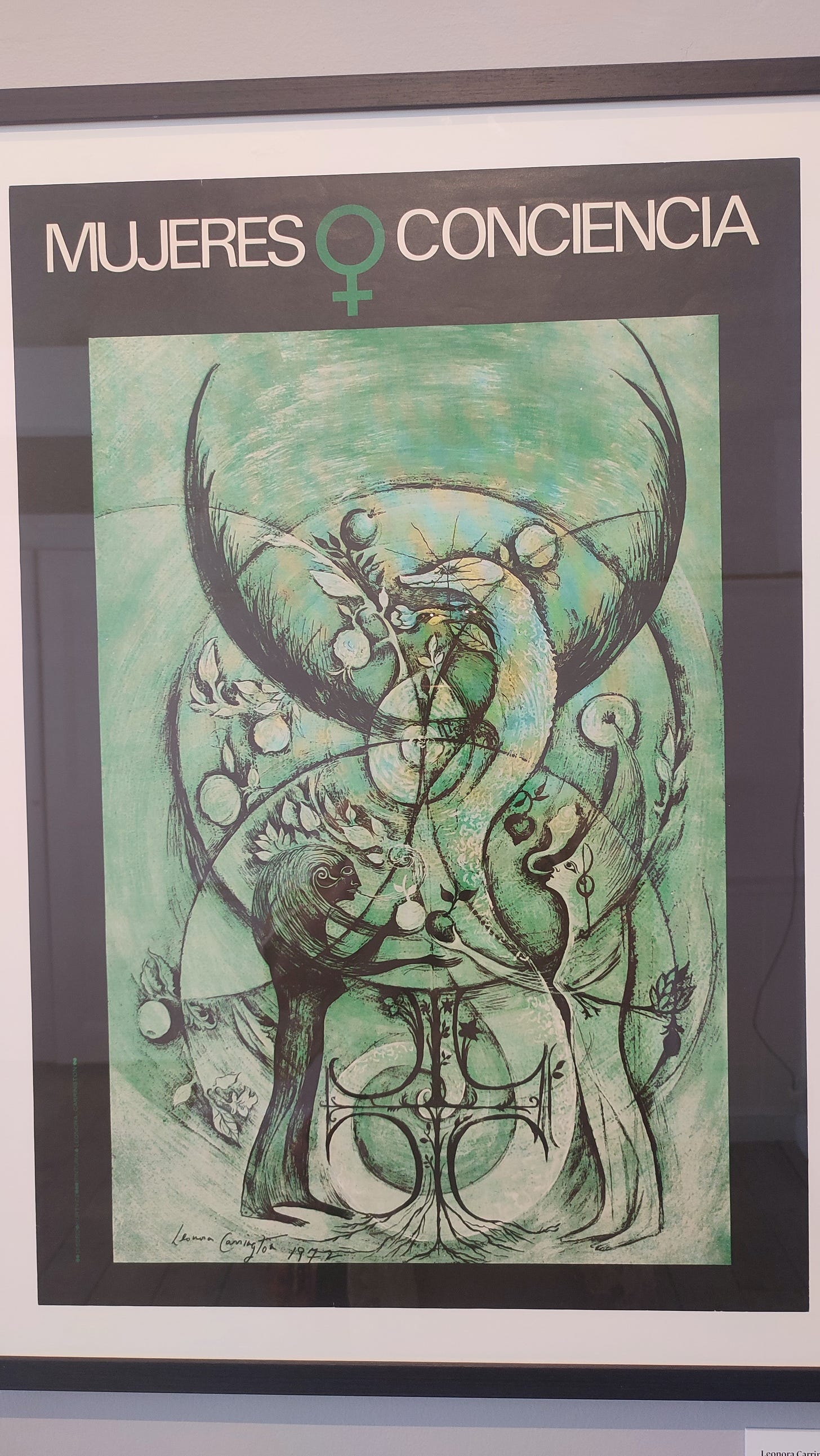

In Mexico, Leonora found a new freedom. She was able to paint without the constraints of European society, and she was inspired by the country's rich culture and history. She later became involved in the late 1960s feminist movement, and she designed a poster called "Mujeres Consciencia" (Women's Awareness).

Leonora's work is full of references to Mexican art and mythology. She was particularly interested in the Mayan civilization, and she spent time in Chiapas researching the region's art and culture. She was also influenced by a wide range of other sources, including Catholicism, fairy tales, Irish myths and legends, Kabbalah, the Occult, Tarot, Buddhism, and Aztec history and traditions. In 1948, she read "The White Goddess" by Robert Graves, which had a profound impact on her work.

The book's eponymous deity was a triple goddess, and after reading it Leonora's work often included a trio of women. In some works they represent the goddesses of the sky, the earth and the underworld; in other works, they are the girl, the mid-life woman and the "crone," as Leonora called the wise later-life female humans on whose actions she believed the future of the planet rested. One could argue that she was an early eco-feminist.

"Most of us, I hope, are now aware that women should not have to demand Rights. The Rights were there from the beginning: they must be Taken Back Again, including the Mysteries which were ours and which were violated, stolen or destroyed."

Long before Leonora was in her eighties or nineties, she was fascinated by the state of women in later life. Her novella The Hearing Trumpet, written when she was in her fifties and published in 1974, tells a fantastical tale of a liberated, magical and adventurous later life.

Many elements of life with Leonora in her house in Mexico City in her nineties were reminiscent of the story of her protagonist Marian Leatherby, aged 92, in The Hearing Trumpet. Leonora's attitude was as Marian's: a rebellion against old age, and against all the expectations of what later life should be. She thought later life should be no less an adventure than youth; and she was determined to prove it could be. In her final years in her house in Calle Chihuahua in Mexico City, Leonora was no longer able to paint. But she continued to create, until the last weeks of her life: she sketched, she designed jewellery and she made sculptures.

In old age, as in earlier decades, she worked at the kitchen table or the dining room table, sketching each sculpture. The pieces were then modelled in wax or plasticine: for a time, an assistant helped her, and the garage was converted into a workshop. When the pieces were being cast at the foundry, Leonora would visit to check on their progress.

Leonora completed her last drawings and models in the early weeks of 2011, before becoming unwell in the spring. She died in hospital in Mexico City on 25 May.

Her life was an adventure to the end, played out in her artworks as well as in her ability to live entirely in the moment, making the most of every day. She is buried in the English cemetery in Mexico City.

"I often feel I am being burned at the stake just because I have always refused to give up that wonderful, strange power I have inside me."

In my Surrealist Survival Kit, I shall place:

My Mexican rattle; my Leonora tarot; my dried toad purse from Las Pozas, Xilitla; a jade dragon, a beaded necklace; my runes, some rose petals and a perfumed flint hag stone.

What will you place in yours?

Wishing you lots of love as always.

Serena xxx