Another Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday has passed. This year was marked by the huge peace march in London calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, where over 10,000 civilians, so many of them children, have died at the hands of the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) in a war declared on Hamas in response to their devastating attacks on Israel that launched on my birthday 7 October, killing 1,400 people, mainly civilians.

It is too much to bear, to witness the suffering of so many people. I take refuge in prayer, in lighting candles, in recalling the vision of Shu Bat Yam that I had a week or so before the 7 October attacks. Shu Bat Yam means the daughter of the sea bringing comfort. She is a sea spirit from the coast of Bat Yam, which is an Israeli coastal city not far from Gaza. It took a direct missile hit on that fateful Saturday. My vision was of this sea spirit who told me her name as she rose out of the water. I had never heard of Bat Yam before or its meaning in Hebrew. It was as though she offered a premonition of what was to come, and that so much comfort to so many along that coast and inland is what is needed right now. Here is the galdralag spell poem that she sang to me:

She sings to you

from the shining sea

black hair blowing brightly.

Your yearning youthful

years fall away,

the threshold thrusts open before you.

Your potent powers be praised.

I remember as I always do at this time of year, my own family’s stories of the horrors of war. Both my grandfathers served in the First and Second World Wars, in the army and Royal Flying Corps/RAF respectively. Mercifully, they both survived, and I knew both as a child. They never spoke to me about the war. My grandmother recalled her father’s memories of the first war, in the Navy, aboard convoy ships. She remembered how in WW2 her parents’ house in Keyham, Plymouth, took a direct hit in a bombing raid during the Blitz. They lost almost everything. I have one of the few surviving pieces of furniture, a small chest of drawers my great-grandfather Samuel Gooding made for my mother. It still has the crack from the rubble falling on it.

This poem is based on the story my grandmother told of her father in WW1, and that of her Uncle Stan, her mother’s younger brother, who died in the cavalry charge at the Battle of Mons, leaving three orphaned children.

Resurgam I

I can hear the horror

of drowning horses,

along the Cornish Atlantic coast.

War horses,

destined for the front-line

mud of Flanders fields.

Cargo for men

to slaughter

other men.

Stan was horse-mad,

a lithe 9th Lancer.

Edith sobbed when

she received the card:

missing in action.

Her younger brother,

held the cavalry charge

like knights of old

without their armour,

just a sword, a lance

and his horse set

against the bullets and bombs.

Years later, she met a man

who had seen Stan's

head blown off at Mons.

Finally, she was able

to start grieving.

Samuel never forgot

the convoy ship

crowded with

a thousand horses.

Their desperate, screeching whinnies,

more haunting even

than the sounds

of drowning sailors

off the coast of Chile,

his friends aboard

HMS Monmouth,

734 lives lost in cold water.

Torpedoes broke

through the lines of protection;

his ship that saved

so many from a similar fate,

could not save these horses

or his matelot mates.

Their drowned ghost manes

still flail the waves

crashing the Cornish coast

in Manannan's cavalry charge.

Resurgam is their battle cry.

This morning I drove over to St Andrew’s church, Bishopstone, a small hamlet near Seaford, tucked away in a South Downs valley between two hills, within view of the coast. It is the most beautiful early Anglo-Saxon church, full of treasures and stories. More of which I’ll write about here, as they are currently the subject of my talk at the Catalyst Club entitled The Saint, the Psychic and the SheelaNaGig.

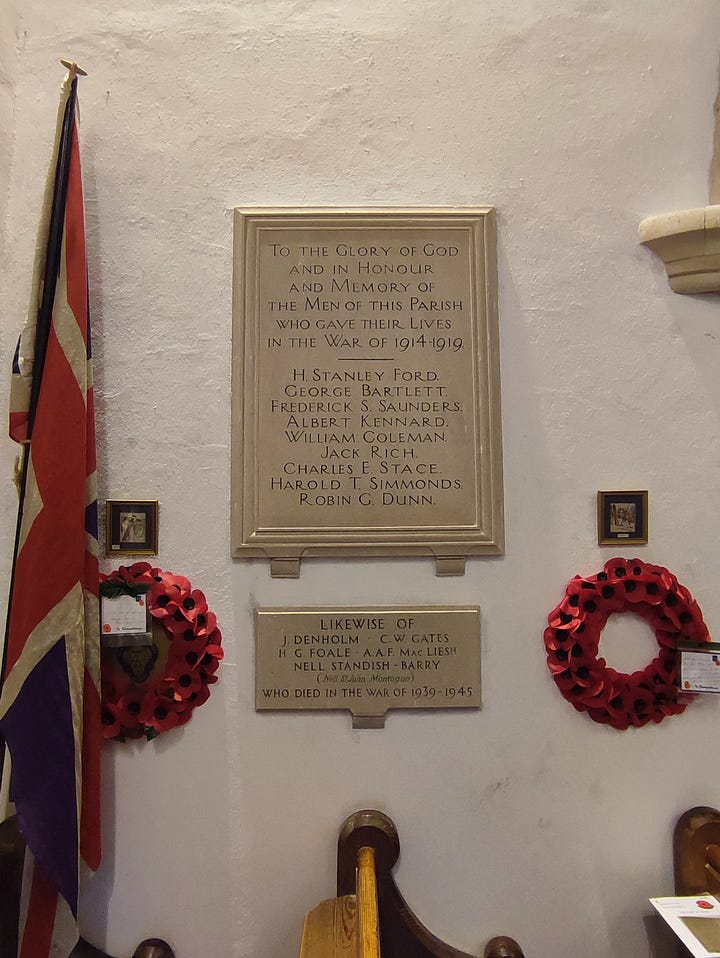

Since 2020, I’ve been tending the forgotten grave of a remarkable woman, Nell St John Montague. She was said to be a WW2 spy, who with her clairvoyance, foretold her death in a fiery flame. She died on 23 August 1944 when a doodlebug fell on her South Kensington house. She was a regular visitor to St Andrew’s when staying in her summer home, Lulleen on Seaford Esplanade. That is why she is buried there. Nell was a fascinating woman, a contemporary of my great-grandmother, whose house was destroyed in the war. Nell was born in India and was sent to an English boarding school as a child. She was aware of her mystic powers from an early age. She became an actress, playwright, author, and celebrity fortune teller. She predicted the death of Lord Kitchener a few weeks before he died as his ship HMS Hampshire, struck a mine off the coast of Orkney.

She is remembered on the war memorial as a civilian who died in service in WW2. Hence the rumours she was a spy, with her powerful political and international connections.

I paid my respects to Nell, laying flowers on her grave, and decorating the tree above it. I hope to be returning soon to hold a storytelling evening in aid of church funds.

As I arrived home, the remembrance service at Hove War Memorial on my street was just starting. I bumped into my recent acquaintance, Yusef, who had arrived on Brighton’s shores in a small boat last October, a refugee from the civil war in Sudan. He told me he had finally been granted asylum, so now he could look for work. His family, however, remain in Sudan. At least there was one piece of good news. We watched the service together. We both prayed for peace.