(NB the podcast is the Song of the Birchmother (read on) and not about Ithell. But I'm sure Ithell worked in this way too as a channel. I can't change the title!)

I really enjoyed taking a riverboat from Tate Modern in London down to Millbank to Tate Britain after a workshop at the Financial Times last week. The reason I went to Tate Britain was to see a new exhibition of the work of artist, visionary writer and occultist Ithell Colquhoun. It was a joint exhibition with the work of Rye artist Edward Burra, whose art made a great impression upon me when I was 16 and saw an exhibition of his paintings in Southampton. I remember driving there in my boyfriend's 2CV, listening to Lloyd Cole and the Commotions and feeling very intellectual and artistic. I shall save writing about Edward Burra for another letter. Today I want to take a look at Ithell's work, weaving some of the show notes from the V&A exhibition with some further research into her work, especially around divine union, sex magic and tarot.

I think Ithell may have had synaesthesia. She was certainly interested in experimenting with colour and a felt embodied sense of colour. I have been writing recently about my synaesthesia and somatic work and Ithell's paintings completely vibrate with me. I could spend hours just looking at them. I really like her writing, the fact that she settled in Cornwall at Lamorna Cove and her enduring connection to the Nine Maidens stone circle. I remember running in circles around the Nine Maidens many years ago, and of course Cornwall is another ancestral home for me. It's a heart home. I always feel very alive and at peace when I am in Cornwall.

Ithell's Taro is so beautiful. Again, that totally resonates with how I see colour. Her tarot deck represents how, when I am in meditation or in trance or receiving massage or healing or in a vision journey, I see and feel and sense colour internally. This is what I am seeing in my third eye, in my body, in my cells. How she interprets colour for the tarot in this way feels so resonant, intuitive and radical.

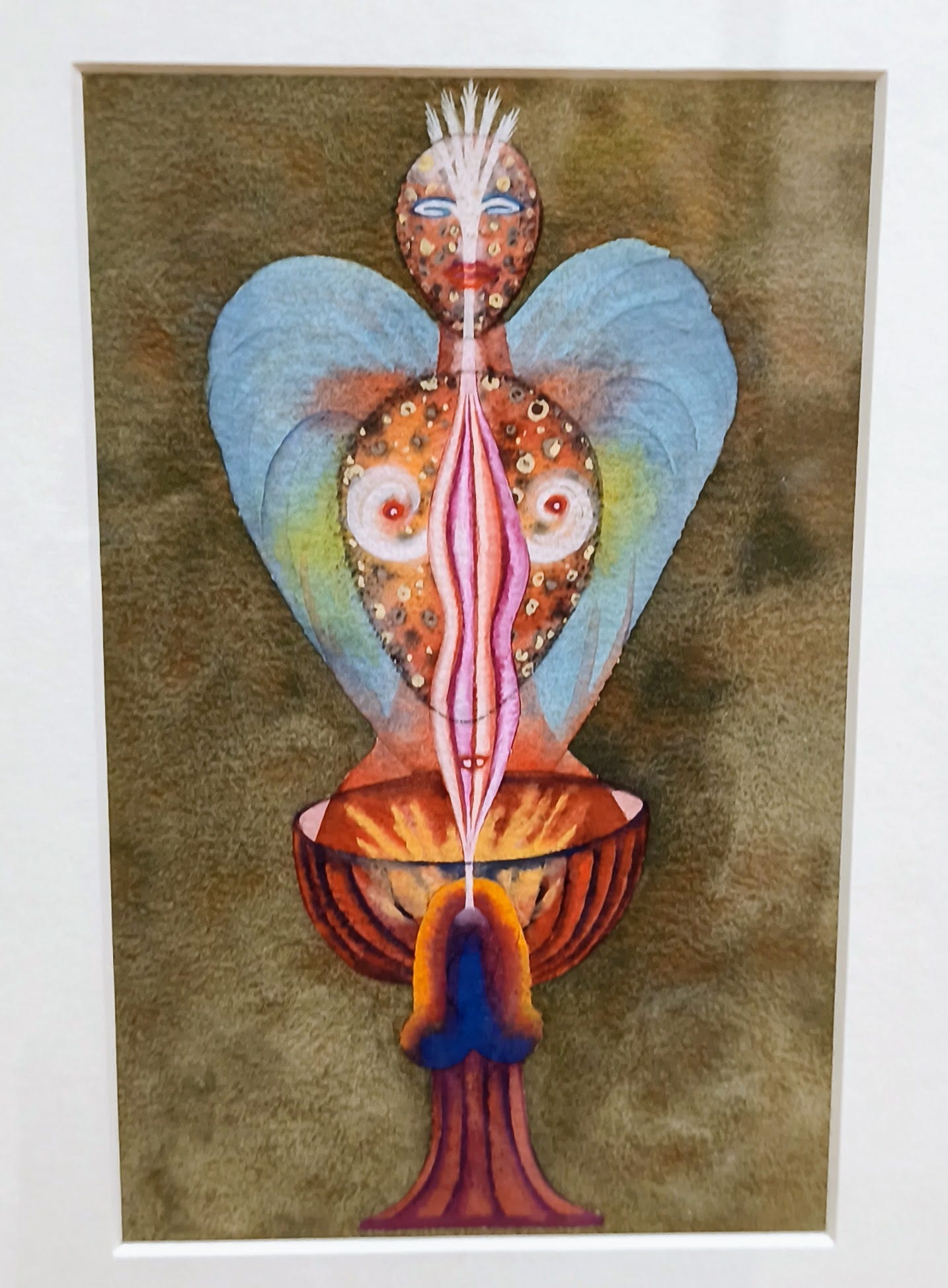

I am entranced with her divine union of the masculine and the feminine, the representation of divine love as she was tapping into tantra and an approach to physicality that is spiritual, sensual and a celebration of the highest self in union with another higher self. This is far removed from the commercial representation of sex and sexuality. How the act of sex is transcendent, can transcend and create a direct channel with Great Spirit, and how that combined energy and the falling away of ego can be used as a form of healing. For the artist to represent this through her art, and for a woman to do this in the 1940s, again feels ahead of its time, visionary and evolutionary.

Some artists paint what they see, and then some paint what others cannot see at all. Ithell Colquhoun (1906-1988) belonged firmly to the latter category, creating a body of work that served as both artistic expression and magical practice, windows into dimensions that conventional reality barely acknowledges.

For too long, Colquhoun's extraordinary legacy has dwelt in the shadows of art history, overshadowed by her male surrealist contemporaries and dismissed by those uncomfortable with her unapologetic embrace of the occult. But as cultural attitudes shift and we begin to recognise the esoteric spiritual dimensions of more modern artistic practice, Colquhoun emerges as a visionary whose time has finally come. Read the essay about her work further down the letter.

Solstice Reflections and Ancient Connections

London was very hot as we approached the midsummer solstice, which has now just peaked here in the Northern Hemisphere. The longest day is so important—it brings us so much light in a world where winters are so long and dark. We celebrate the sun before she begins her descent again into the Underworld. And note that I said she and not he, for in Scandinavian traditions and cosmology, the sun is feminine. She is known as Sunna and in the runes is represented by Sowilo, or Sol.

Having grown up with the sun as masculine energy in the Celtic tradition— and honouring Cernunnos, the horned god of fertility, life, animals, wealth, and the underworld, through the Celtic wheel—I find it challenging to think of the sun as feminine and the moon as masculine, despite also growing up with "the man in the moon." I see the moon as feminine and the sun as masculine, but after spending a beautiful day in the Sussex birchwood for part two of our three-part Norse Wisdom summer celebration in Fittleworth, I'm beginning to work with the sun as both feminine and masculine.

In the birch wood on the solstice, we were given an exercise to sit with a tree and connect with its heart. Most of our small group felt the tree's heart was where the trunk meets the earth, just above ground level, not higher up in the crown, despite how long and thin yet strong and graceful the upper branches are. The exercise required us to ask permission: can we work with this tree, can we enter its heart? We were to receive a gesture, sound, and symbol that would remain secret, keeping our eyes open rather than closed to stay rooted as we journeyed to the heart of the tree to receive whatever healing or message it might offer.

I found a tree I connected with deeply—possibly one I'd worked with during my Utiseta practice last year. It felt familiar, and I quickly received the gesture, sound, and symbol. Sitting with the tree's heart, I connected in and what emerged was a song in two parts. The first part ran eight and a half minutes, which I've shared as an audio podcast for those interested in this conscious trance practice. (The nightingale is from Essex and mixed into the recording)

The voice that came through surprised me—so high, when I don't naturally sing in a high register. The words simply flowed, carrying the voice of an ancient energy present in the wood as the Birch Mother. The message was beautiful and clear: sing to the trees. This has come through before in my work with ancient energies—the trees want feeding, which means they want human love. If we love them, they love us in return. They are our lungs, vital for life, requiring a strong, loving, reciprocal relationship. Tree management is acceptable too—we need both wild wood and wilderness alongside managed woodland, but it must be in balance.

The second part was deeply personal: I received a recipe for a healing spell to bury at the tree's heart-root, speaking the intention for what needed healing before releasing it. I followed this recipe at the workshop's end, and remarkably, that very solstice day the healing manifested. The power of the sun, the beauty of the woods—such a magical solstice weekend.

I also completed my Oracle of Vinyl today 22 June. The playlist features one song from each record pulled through thirteen days. You can follow the insights and mantras for this thirteen-day ceremony on my Instagram. There will be a part two later this summer, and I've thoroughly enjoyed rediscovering my record collection this way, inspiring others to do the same.

This evening I'm attending the book launch for a collection of sacred Sussex walks, which includes my small entry celebrating the long-forgotten only female saint of Sussex, St Lewinna—an early Christian convert martyred for her faith with a fantastic tale attached. Her shrine was in Bishopstone, in a church where I've worked with the beautiful energy there. This forms the basis of one of my talks, so I'm excited to have this entry in the book. You can buy it on Amazon

Tomorrow I'm heading to Kingley Vale after work to spend time with the 2000-year-old yew trees.

This poem also came through for the solstice:

The Tree Planter

You who are the tree planter sit in the high branches

of the great tree Yggdrasil silently watching

through veined greenery the comings and goings

of the cloud walker the cloud warrior

as she drums for the fire in her blue eyes

reaching toward the sun on eagle's back

with hummingbird at her shoulder

Sunna, Sowilo, solstice sun

feminine in the North masculine in the South

birthing her daughter to bring golden-hearted strands

of hair down to Earth where the sun dancers

heave to the beat hanging from the lower branches

of the same great tree in which you sit

Ithell Coloquhoun: Between Two Worlds From Birth

Born in Shillong, India, to British colonial parents, Colquhoun's life began with the experience of existing between worlds—a theme that would define both her art and her spiritual practice. Raised in Cheltenham after leaving India as a child, she carried within her what she described as "an enduring connection" to her birthplace, a sense of geographical and cultural displacement that she would ultimately transform into a source of mystical power.

This early experience of liminality—of existing at the threshold between cultures, between the rational British world of her upbringing and the more mysterious East of her birth—prepared her for a lifetime of navigating the spaces between the seen and unseen, the conscious and unconscious, the material and the spiritual.

The Making of a Magical Artist

Colquhoun's formal artistic education began at Cheltenham School of Arts and Crafts (1925-7) before moving to the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London (1927-30). But while she dutifully studied life drawing and painted classical subjects, her true education was happening elsewhere. Even as a young artist, she was drawn to alternative spiritual groups like the Quest Society and, crucially, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an influential order that taught ritual magic to men and women equally.

The Golden Dawn would prove formative to Colquhoun's development as both artist and occultist. This esoteric order, founded in the late 19th century, synthesized elements from Kabbalah, alchemy, astrology, and Egyptian mysticism—all traditions that would later surface in Colquhoun's art. More importantly, the Golden Dawn treated magical practice as both an art and a science, viewing ritual and symbol as technologies for accessing higher states of consciousness.

Surrealism and the Sacred Feminine

In 1931, Colquhoun encountered surrealism firsthand during a brief stay in Paris, where she was particularly inspired by Salvador Dalí's "unconventional ideas and meticulously painted imagery." But her surrealism would develop along distinctly different lines from her contemporaries. Where male surrealists often focused on the liberation of masculine desire and the conquest of the feminine unconscious, Colquhoun's work celebrated what she saw as sacred feminine power suffusing both body and landscape.

Her breakthrough came with the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, where she attended Dalí's famous lecture delivered while wearing a diving suit. This event catalyzed her Méditerranée series—dreamlike paintings she considered her first true surrealist works. But even as she joined the Surrealist Group in England in 1939, tensions were brewing.

The conflict came to a head in 1940 when E.L.T. Mesens, leader of the British surrealists, prohibited members from joining other societies, including occult orders. For Colquhoun, this was an impossible demand. Her artistic practice and her magical work were inextricably linked, two aspects of a single spiritual quest. She chose her occult studies over surrealist orthodoxy and split from the group.

The Revolutionary Art of Sex Magic

Perhaps the most groundbreaking aspect of Colquhoun's work lies in her development of what scholars now recognise as a sophisticated system of sex magic expressed through visual art. From about 1939 to 1943, surrealist and occultist Ithell Colquhoun produced a significant number of esoteric erotic works that point to the development of a system of sex magic. It is remarkable in that it is likely the first time that an occult practitioner has left a visual record of theorising about a sex magic practice.

Her Diagrams of Love series (1940-1942) represents this fusion of sexual mysticism and artistic practice most clearly. Works like Heart of Corn, concerned with themes of sacrifice and rebirth, and The Bird or the Egg, depicting healing and regeneration, employ sexual imagery not for titillation but as sacred symbols of cosmic forces. British artist Ithell Colquhoun's uncanny paintings are full of androgynous gods, murderous goddesses, yoni-like fruit, and disembodied, fleshy parts floating across hallucinatory, dreamlike landscapes.

Central to this work was her exploration of the alchemical concept of the Divine Androgyne—the union of feminine and masculine energies that represents psychological and spiritual wholeness. This wasn't merely an artistic metaphor but an actual magical practice, with Colquhoun using her art-making process as a form of ritual designed to invoke and embody these transcendent states of consciousness.

The Mantic Stain: Art as Divination

Colquhoun's most innovative contribution to both art and occultism may be her development of what she called "the mantic stain"—a technique that explicitly linked surrealist automatism with divinatory practices. In her 1949 essay of the same name, she compared automatism to divination, describing it as "the perception of future events or forces beyond our earthly senses."

Using the automatic process of decalcomania—applying ink or paint to a surface, then pressing another surface against it—Colquhoun created abstract images that she would develop into finished compositions. But this wasn't simply art-making; it was a form of scrying, using the chance patterns created by paint and pressure as a means of accessing prophetic visions and hidden knowledge.

This technique represents a profound synthesis of artistic and magical practice, treating the canvas as both artwork and oracle, the studio as both creative space and temple. Colquhoun's work dissolves conventional frameworks of gender, art, science, and spirit. She crafted a language in which imagination was not fantasy but a form of knowledge.

The Taro as Pure Color

In the 1970s, Colquhoun created perhaps her most radical magical tool: a complete tarot deck that dispensed with traditional figurative imagery in favour of pure colour and abstract form. In 1977, the Newlyn Gallery in Cornwall exhibited a series of 78 taro designs quite unlike any previous. Ithell Colquhoun's bold project seeks to dispense with the figurative narratives of the traditional tarot and re-imagines the forces behind each card as pure colour.

The cards of this Taro are reminiscent of Rorschach ink blots. The images were made by pouring enamel paint onto a flat sheet of paper, using the same dripped enamel technique she had developed for her volcanic landscape paintings. Following the group's colour symbolism, her deck ascribes colours to each of the four suits: swords are pale yellow, cups deep blue, wands scarlet and disks, or pentacles, are indigo.

This revolutionary approach to tarot design reflected Colquhoun's belief that the essential forces represented by the cards could be more purely accessed through colour and form than through conventional symbolic imagery. Each card became a meditation on the vibrational qualities of colour, a tool for direct mystical experience rather than interpretive divination.

Cornwall and the Ancient Powers

From the 1940s onward, Colquhoun found her spiritual home in West Cornwall, where she gathered inspiration from ancient sacred sites and Celtic folklore. This landscape, saturated with prehistoric monuments and pagan history, provided the perfect environment for her synthesis of ancient wisdom and contemporary art.

Her later volcanic paintings, created with dripped enamel paint, weren't simply landscapes but alchemical symbols—volcanoes representing states of magical transformation, the earth's eruptions mirroring the psychic explosions necessary for spiritual awakening. Living among the stone circles and burial chambers of Cornwall, Colquhoun tapped into what she saw as an unbroken tradition of earth-based spirituality.

The Tesseract and Higher Dimensions

Throughout her career, Colquhoun remained fascinated by the concept of the tesseract—a four-dimensional cube that she believed could provide access to alternative planes of experience. This mathematical concept became for her a spiritual tool, with her studies leading to "the expression of divine energies through diagrams, colours and abstract shapes."

This exploration of higher-dimensional geometry reflects the sophisticated nature of Colquhoun's occult practice. She wasn't simply dabbling in mysticism but engaging seriously with complex metaphysical concepts, using both ancient wisdom traditions and cutting-edge mathematical ideas as tools for consciousness exploration.

Legacy of a Visionary

When Ithell Colquhoun died in 1988 at age 81, she left behind a unique legacy—thousands of artworks, writings, and magical documents that testify to a lifetime spent exploring the intersection of art and spirituality. Her bequest of occult works to the Tate and her studio contents to the National Trust (later transferred to Tate in 2019) created the world's largest collection of materials from this remarkable mystic artist.

With the 2019 acquisition by the Tate of Colquhoun's tremendous 5,000-piece archive, previously held by the National Trust, Colquhoun is about to emerge from the shadows. For decades, she maintained a reputation in occult circles while remaining largely unknown in mainstream art history. Now, as interest in esoteric spirituality grows and we begin to recognise the profound connections between artistic and mystical practice, Colquhoun's visionary work is finally receiving the attention it deserves.

Why Colquhoun Matters Now

In our current moment of spiritual seeking and artistic experimentation, Ithell Colquhoun's work offers something invaluable: a model for how art can serve as a genuine spiritual practice, how creativity can become a technology for consciousness transformation. Her fearless synthesis of surrealism and occultism, her development of sex magic as artistic practice, and her creation of new forms of divination through abstract art inspires contemporary artists seeking to reclaim the sacred dimensions of their work.

More than this, Colquhoun's life demonstrates the possibility of living as an integrated magical being—someone for whom there is no separation between spiritual practice and daily life, between art and magic, between the personal and the cosmic. In a world increasingly hungry for authentic spiritual experience, her example reminds us that the sacred has never left—it has simply been waiting for us to develop the eyes to see it.

For those of us who work with her Taro, who study her paintings, or who seek to follow her example of integrated spiritual-artistic practice, Ithell Colquhoun remains what she always was: a guide to the invisible realms, a cartographer of consciousness, a reminder that art at its highest is always a form of magic.

The legacy of Ithell Colquhoun challenges us to reconsider the boundaries between art and spirituality, between the rational and the mystical, between the seen and unseen worlds. In her paintings, we find not just beautiful objects but actual doorways—invitations to step through the canvas into dimensions of experience that our souls remember.

Sources and Further Reading

Primary Exhibition Sources:

Tate Britain Exhibition: "Ithell Colquhoun and Edward Burra" (from June 2025)

V&A Exhibition Notes (referenced in article)

Academic and Research Sources:

Amy Hale, "Ithell Colquhoun's Erotic Occult Art," Journal of the Western Mystery Tradition (2013)

Dawn Ades, "Surrealism and the Occult," in The Occult in Twentieth-Century Art

Richard Shillitoe, "The Tarot of Ithell Colquhoun," Galleries Magazine (1988)

Tate Archive Collection: Ithell Colquhoun Papers (acquired 2019)

Books on Ithell Colquhoun:

Peter Davies, Ithell Colquhoun: Genius of Place (Sansom & Company, 2015)

Amy Hale, Ithell Colquhoun: Pioneer of Surrealism and the Occult (Strange Attractor Press, 2020)

Contemporary Reviews and Articles:

Various contemporary art criticism and reviews from galleries and museums

Scholarly articles on British Surrealism and occult art practices

Exhibition catalogues from Newlyn Gallery (1977) and other venues

Note: This article combines personal reflection with research from multiple sources to explore Colquhoun's unique contribution to art and occult practice.

Sending you much love as always

Serena xxx

Share this post